The history of technology and its role today

Note that my letter makes zero use of LLM or other “AI” technologies as a matter of principle. I see this as necessary for respecting the dialogue between people.

What is technology, really?

The introduction of new technology is a political and economic phenomenon, but it is often imagined as something above us, as inevitable progress. To paraphrase the social historian David Noble, technology seems to have a life of its own, when we ignore the process of its promulgation and submit to it. It seems to follow a straight line, when we yield to its masters. It seems to impact society from outside when the human aspect is ignored or obfuscated. Against this, we must see technical development as politics.

Computing as we know it is entirely a military invention, and is a field of technology employed first of all in command and control. It shifts leverage from workers to management, and thus from labour to capital. The same was true of the first textile production machines, which reduced the skill required, and therefore the worker’s leverage, in the production process.

Private property of the means of production means that tools (of all kinds), machinery, land, and buildings (those land and buildings used for commercial/industrial economic activity) are not managed in a democratic way. They are owned by individuals who do not need to even lay eyes on them for it to be “theirs” - and not the property of workers tasked with using them, nor the society relying on and affected by their use. Private property is distinct from personal property, which describes possessions from your home to your toothbrush, and the absolute vast majority of people worldwide have no private property. Conflating the two serves to obscure the difference and justify private property.

Our economy is composed of enterprises that range from petty fiefdoms to huge productive dictatorships, from local mechanic shops to Walmarts, all with unelected, unaccountable, and truly authoritarian leadership at the helm. Their focus is profit, the growth of their capital, and when they are restricted from doing harm to people or the natural world it is because of the centuries of political struggle by people like us to set and maintain limits. Still they collude and commit all manner of crimes.

“How will people support themselves?”

Because we are dependent on leasing our ability to work, our situation becomes more precarious when the need for labour-power decreases. Increasing technological productivity does not benefit us, it benefits the class that owns that technology, growing their capital. Over the last 200 years in the capitalist world, as capital grew, the amount spent on labour power grew, but became a smaller and smaller proportion of capital employed.

Now we are in a stage of capitalism defined by monopoly, and are gradually running out of things to profitably invest in. Consequently, finance capital overtakes industrial capital, and war, conquest, and destruction become more and more important forms of investment.

We have material abundance but a system which is structured to maximize corporate profits rather than meet social needs. Therefore what looks rational and organized is really irrational, a product of happenstance, and an unsustainable future. In 1930, Keynes dreamt that revolutionizing productivity would lead his grandchildren’s generation to work less and less, such that by 2030 we might have a 15 hour work week.

Was he mistaken or intentionally misleading? This hasn’t happened and instead productivity increases pile on corporate wealth. Similarly, we are not in a position for automation to make us wealthier and more secure, but actually to do the opposite. If social production was socially owned, and benefitted us all, new steps in automation would be cause for celebration.

“Do we need universal basic income (UBI) to sustain people once their jobs are replaced by technology? What are people going to do to keep themselves occupied?”

UBI as cash payment has been demonstrated by social scientists to change lives in a marked and positive way. If it were rolled out, life would get a fair bit better for many people in many ways, but significant problems would remain unsolved. It does not solve the problem of working class precarity manifested in dependence on wage labour, just pad some of its evils, like other welfare measures do.

A full rollout would boost consumer spending, very important in wealthy, monopoly-capitalist countries. Through a more critical lens it can be seen that this amounts to a cash transfer to landlords, mortgage holders and consumer goods oligarchs like those helming Walmart, Amazon, and Loblaws. We would get relief from UBI as much as we’d be able to pass it on to those enterprises that dispense their food, housing, and other needs. We’d also be able to spend a bit more time and be more selective searching for a job.

When the chips are down, UBI is vulnerable. It would be treated as a threat by political hegemony. When reaction sets in, payments could be cut, or held in place so that inflation decreases their purchasing power. We need to elevate this to a struggle for human rights, to make it something bigger and harder to roll back.

A universal basic needs guarantee is the goal I propose we set for ourselves, one that can grasp the problem by the root. Instead of mere social assistance, we could strike at the profit motive and take back elements of our humanity. We could secure education, adequate housing, all basic needs including health, leisure time, and dignified work for the able, as rights of everyone in our society. Democratic economic planning mechanisms could replace the autocratic petty fiefdoms of profit-seeking businesses in all these sectors.

“The cost of living and the housing crisis are definitely part of the labour shortage, but they are just a symptom of a greater issue — the world is getting older and we are running out of people to staff all kinds of jobs.”

First, I would like to consider the framing of the labour shortage. There are plenty of working people, working plenty of hours. Jobs that go unfilled are not paying enough to attract them. Perhaps they consider their starting pay to already be high, but if the job is going unfilled, it’s your move as a buyer of labour-power to go higher if you want to get it. Wages are determined by both political and economic developments. At the same time the experience of job seekers is that of making dozens or hundreds of applications, going through tedious, labyrinthian web apps to submit applications, to be ghosted far more often than rejected, and rejected far more often than interviewed!

The “world” - global capitalism - should be expected to gradually employ fewer and fewer people. The role that human labour-power plays in productive activity has been diminishing gradually since at least the Industrial Revolution of the 19th century emanating from England. As said above, as capital grows, the amount spent on labour power initially grows, but becomes a smaller and smaller proportion of capital employed, and will eventually decrease absolutely. The fact that resources spent on human’s wages were more and more outnumbered by resources spent on constant capital (raw materials, machinery, equipment) has been obfuscated for a while by the fact that markets grew such that real wages and the wage-working part of the world’s population generally grew.

This growth will run out sooner than later!

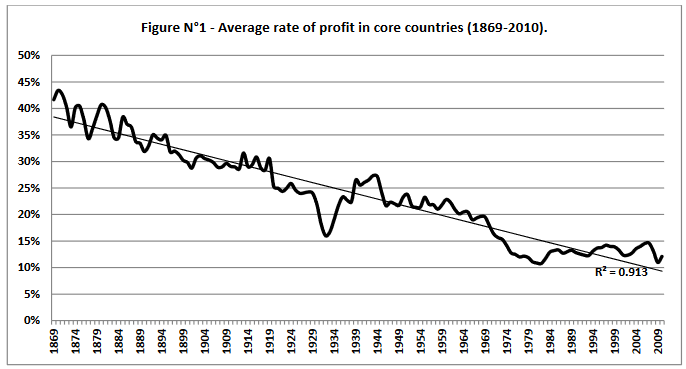

Capitalism is no longer a dynamic system, and globally the rate of profit is in decline. At the 2023 conference of the Italian Association for the History of Political Economy, social scientist Tomas Rotta presented his findings that the global rate of profit has indeed been in sharp decline since the genesis of capitalism, as observed and predicted to continue by Karl Marx in his writings and particularly in Capital. Another scientist, Esteban Maito of Argentina gave the following data in his paper “The Historical Transience of Capital” on this subject.

As time passes we should expect to see more and more difficulty for small business, increasing malaise for big business, and vitally, real precarity and hardship for the working class, by which I mean all those who work for a wage to sustain themselves and do not sustain themselves by owning and profiting from capital investments.

The threat of mass unemployment is built into the logic of capitalism. No economic system is eternal, not slavery-economies of antiquity, nor feudalism, nor capitalism. It must end, either in the reconstitution of society into something better, or our common ruin. Capitalism will not eventually fix itself, but it will eventually destroy itself.

There is an alternative.

Back to the portal...